Behind the Shine: The Red Flags and Risks of the Maldives’ $8.8 Billion Financial Centre Deal

6 މޭ 2025 - 10:18 0

The project is reportedly led by MBS Investments, a little-known Dubai-based family office with no proven track record of delivering large-scale developments.

Behind the Shine: The Red Flags and Risks of the Maldives’ $8.8 Billion Financial Centre Deal

6 މޭ 2025 - 10:18 0

The government’s recent announcement of an $8.8 billion blockchain-based financial centre project—billed as a transformative step for the Maldivian economy—demands urgent public scrutiny. While the headline figure is staggering, the underlying details reveal serious red flags, economic risks, and deep concerns about national interest and fiscal responsibility.

1. A Project That Outsizes the Entire Economy

With a cost greater than the Maldives’ total GDP, the scale of this project is simply unprecedented. For a small island nation with limited institutional capacity, taking on a project of this magnitude poses real danger. It risks turning into a white elephant—expensive to build, difficult to sustain, and offering little actual benefit.

2. Investor Credibility is Weak

The project is reportedly led by MBS Investments, a little-known Dubai-based family office with no proven track record of delivering large-scale developments. There is no clarity on how the funds will be raised, and to date, no actual investment has been made or deposited. Without strong, credible financial backers and public transparency, this project risks collapse before it even begins.

3. All Infrastructure, No Institutional Substance

While the project promises grand towers and commercial buildings, it lacks focus on the core elements required for a genuine financial hub:

- Financial laws and regulatory frameworks

- Licensing regimes and supervisory architecture

Compliance protocols for digital assets and anti-money laundering Without these institutional foundations, the hub could become an expensive but hollow shell—gleaming infrastructure with no real financial activity.

4. Fiscal and Debt Sustainability Risks

A. Hidden Liabilities

Even if the government is not directly funding the project, it may still incur indirect financial burdens through:

- Land lease losses if land is undervalued or allocated without competitive bidding.

- Tax holidays and duty exemptions that forgo critical revenue.

- Infrastructure obligations (roads, power, telecom) that fall on the state.

- Sovereign guarantees or implicit fallback responsibilities if the developer defaults.

B. Future Bailouts

If the project becomes politically tied to the government’s image and ultimately fails, the state may be pressured to step in and rescue it, using public funds. This has been the fate of numerous failed megaprojects in other developing countries—leaving taxpayers to shoulder the cost of investor failures.

5. Government Revenue: Virtually Zero

Contrary to claims that the government could raise USD 500 million through this deal, the project operates under Special Economic Zone (SEZ) provisions. This means:

- No corporate income tax

- No withholding tax

- No capital gains tax

- No customs duties or GST on SEZ transactions

In other words, the government has no guaranteed revenue stream from the project. If there are no upfront land premiums or performance-based fees—and none have been disclosed—then the claim of raising hundreds of millions is either misleading or speculative at best.

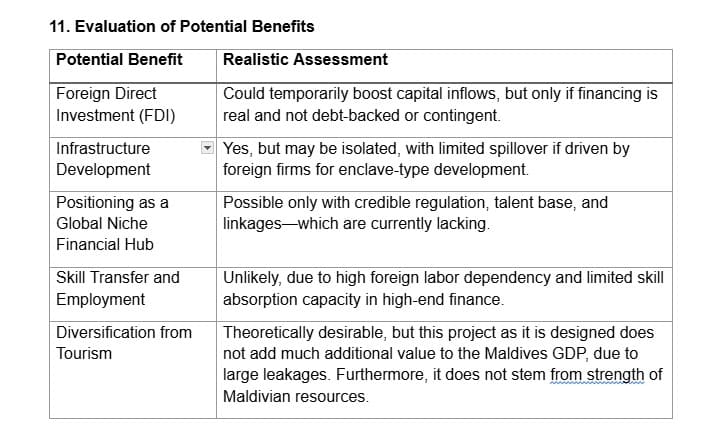

6. Minimal Economic Value for Maldives

Almost all construction materials and labor will be imported, with foreign contractors likely implementing the project. Even during operations, the bulk of employment will go to foreign financial professionals, not Maldivians. Any income generated will likely be repatriated abroad—resulting in significant capital leakage and low value-added to the domestic economy.

7. Tax Base Erosion and Domestic Business Flight

Domestic firms may re-register in the SEZ to exploit tax holidays and reduce their tax burden. Without strong ring-fencing rules and anti-avoidance mechanisms, this could lead to a serious erosion of the domestic tax base—reducing the very revenue the country needs to address its fiscal crisis.

8. A Country in Crisis Cannot Risk This Much

For a financial centre to succeed, macroeconomic stability and a skilled local workforce are essential. The Maldives currently has neither:

- The country is cash-strapped, with critical rationing of public funds, delays in capital spending, and an inability to reduce government expenditure.

- Foreign reserves, while slowly increasing, remain dangerously low—leaving the country vulnerable to external shocks.

- The fiscal situation is dire, and public debt continues to rise.

In this context, taking on a project of this magnitude—with unclear returns and high risk of failure—could further destabilize the fragile macroeconomic environment.

9. Regulatory and Reputational Risks Loom

The promise of a blockchain-driven financial hub may attract unregulated capital and speculative financial actors. If not tightly supervised, the Maldives could become a jurisdiction of concern for illicit finance, potentially triggering the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) grey-listing, the loss of correspondent banking relationships, and a serious blow to the Maldives’ global financial reputation.

10. Where Is the Transparency?

The lack of parliamentary oversight, public consultation, or fiscal risk disclosure is deeply troubling. Such a deal should undergo independent review before any commitments are made. The country cannot afford to walk blindly into a deal that could mortgage its economic sovereignty for speculative promises.

12. Critical Risks and Questions

A. No Evidence of Firm Commitments

There are no signed financial instruments, deposits, or legal guarantees. The Minister of Finance’s claim that the state will generate USD 500 million appears to be based on speculative future cash flows, not on actual, committed revenue.

B. Overstated Expectations

Claiming such revenue raises two possibilities:

- Massive upfront monetization of land, or

- A backdoor deal involving citizenship sales, sovereign leases, or similar instruments.

Either option is risky, potentially bypassing parliamentary oversight and violating fiscal best practices.

C. Fiscal Transparency and Accountability

No explanation has been given as to whether the projected revenue is:

- Budgeted or expected in FY2025, or

- Classified as off-budget or contingent.

If it fails to materialize, the government may face a widened fiscal deficit, leading to deeper borrowing or even default risk.

Conclusion: A Deal That Demands Accountability

If this financial centre project fails to deliver—and many signs suggest it may—the Maldives could be left with empty towers, lost land, no tax revenue, and greater fiscal pressure. Policymakers must put national interest first and ensure that transparency, accountability, and public benefit are at the heart of any development agreement.

It is not too late to demand answers. But if we don’t act now, the cost could be generational.

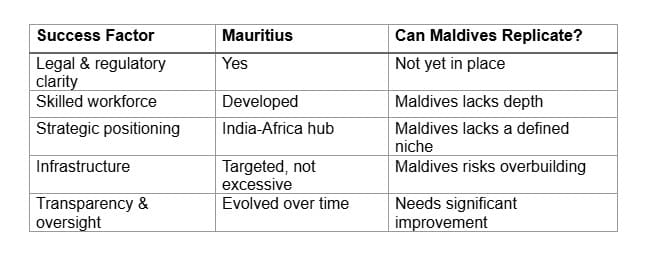

Case Study: Mauritius – A Measured Success Without Mega Infrastructure

Overview

Mauritius has emerged as one of the most successful small island nations to establish itself as an International Financial Centre (IFC). Unlike many countries that pursued flashy infrastructure or speculative developments, Mauritius built credibility through smart policy, regulation, and targeted investments—not massive construction.

Why Mauritius Is Considered a Success

Strategic Legal Framework

Mauritius developed a robust regulatory environment based on UK common law, aligned with international standards (OECD, FATF), and enforced by a credible Financial Services Commission (FSC).

Double Taxation Agreements (DTAAs)

It secured DTAAs with over 40 countries, including India and China, becoming a gateway for investment flows into Africa and Asia, especially in private equity and banking.

Skilled Workforce and Local Participation

Mauritius invested in financial education and bilingual training, producing skilled professionals in law, accounting, and finance—ensuring domestic value capture.

No Overbuilding or White Elephants

Mauritius built Ebene CyberCity and modest business parks—but did not over-invest in towers, mega-complexes, or underutilized infrastructure. Its development was demand-driven, keeping costs and risks low.

Economic Diversification

The financial sector contributes 12–15% of GDP, helping reduce reliance on sugar and tourism.

Challenges and Cautions

Mauritius faced greylisting by FATF in 2020 (removed in 2022), showing the importance of constant regulatory vigilance.

The revised India-Mauritius tax treaty in 2016 reduced flows and exposed the economy’s overdependence on offshore finance.

The financial sector’s benefits are unevenly distributed, concentrated in high-skill jobs with limited broader employment effects.

Lessons for Maldives

A successful financial centre is not built on real estate, but on regulation, trust, and integration with global financial systems.

Infrastructure should follow function—not lead it. Maldives should avoid speculative megaprojects and focus on institution building.

Human capital is key: Without a skilled domestic workforce, value-added will leak abroad.

Transparency and international compliance must be non-negotiable to protect reputation and banking relationships.

Conclusion

Mauritius shows that small island states can succeed as financial hubs—but only with discipline, credibility, and clear national strategy. The Maldives risks failure if it prioritizes buildings over institutions and headlines over substance.

Comment